The Business of Helping Koreans Sleep

More and more Koreans have trouble with sleep. Solutions abound, but will they be enough to address deeper structural causes?

Even though it's right next to the busy Sinsa subway station just south of the Han River in Seoul, one might not think too much about what goes on inside this gold-colored office tower when passing it by.

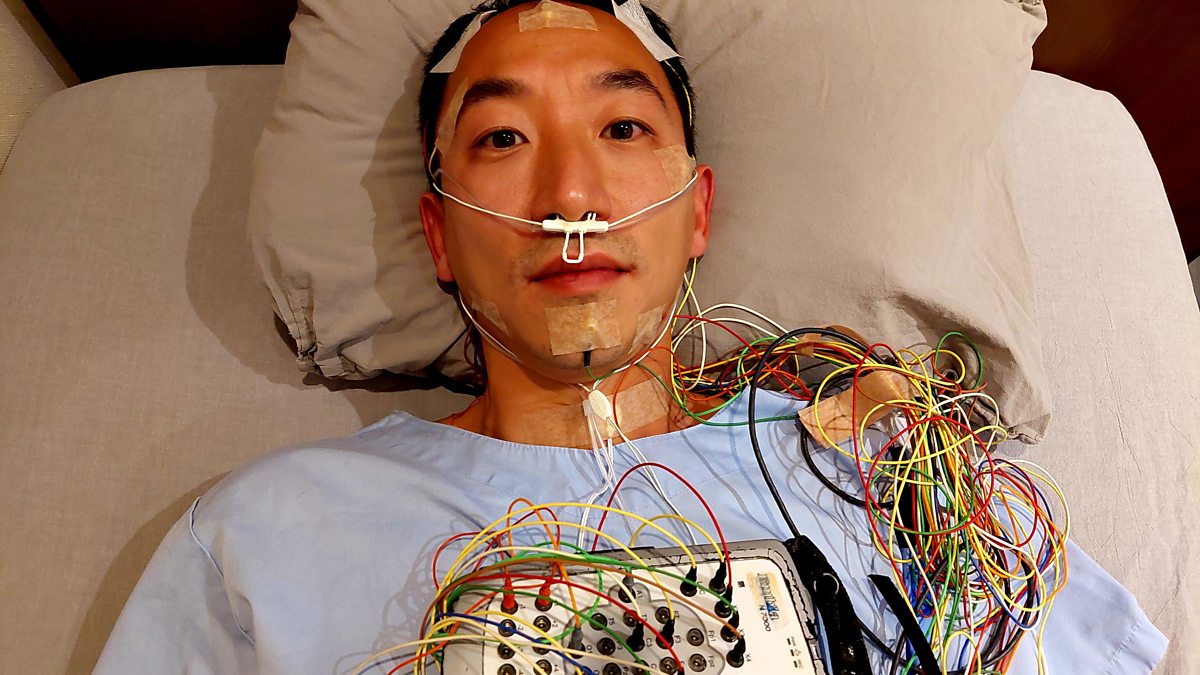

On the 8th floor is Dream Sleep Clinic, where chronic insomniacs come for overnight observation and treatment.

Psychiatrist Lee Ji-hyun runs this place. She is a quiet woman with a gentle smile. Her hair is neatly tied into a ponytail and she wears a tailored white jacket over a long plaid skirt.

It's when she starts talking about insomnia that her voice suddenly becomes animated.

"It's a growing problem here in Korea," she says. "Comparing the insomnia patients from 2002 ... to 2012, there was double the number. And afterwards an 8 percent increase every year."

Looking around the country, it's hard to imagine that sleep is such a serious issue. To me, Korea means active nightlife, people drinking (and vomiting) at late hours, and fighting hordes of other people to get a taxi home when the third or fourth round of merrymaking is over, around 2 or 3 am.

But while all this is going on, there are many others in bed, struggling to fall asleep. It makes sense, explains Dr. Lee:

"The psychological demand or stress is very high in Korea, and so is the workload. Also, there is an abrupt or frequent shift in working hours. People are asked to work late or work during other hours."

Add to that the nightlife, a great public transportation system that runs late, and people trying to compensate for the lack of rest by sleeping more on the weekend. It's a perfect recipe for an irregular sleep pattern, she says.

While reporting for a BBC radio documentary on this same topic, I came to see her point, mainly because of the scale of the industry and all the services—Dr Lee's included—for the sleepless on offer. Without demand there can be no supply.

"The psychological demand or stress is very high in Korea, and so is the workload. Also, there is an abrupt or frequent shift in working hours. People are asked to work late or work during other hours."

Almost 100,000 Koreans are taking sleeping pills. That's according to the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service (HIRA), which assesses claims filed with the Korean national health insurance. Without exaggeration, almost everyone in Korea is covered by this public insurance system. It makes HIRA a reliable source of data for understanding Koreans' health issues.

HIRA says that in March 2021—that's the most recent period for which data is available— about 92,000 people were treated by doctors for difficulty with falling and staying asleep. This is the usual category doctors click in the system when they prescribe sleeping pills.

My mother has also suffered from insomnia as long as I can remember, but it's gotten worse in the last six, seven years. I know because I see her sometimes take tablets for it.

"Even though I'm lying down on the bed, I'm always hesitating if I should take a pill or not, and after a while, I will take a pill," she says.

The medicine she used to take is called Stilnox or Zolpidem. It's known better in the US by its brand name Ambien. This particular medicine was the go-to prescription for most Korean insomniacs until a few years ago. Then reports began surfacing about various possible side effects including memory loss and hallucination.

In 2015 a thirty-something businessman drove a car into multiple vehicles in the middle of Gangnam allegedly under the influence of Zolpidem, which he had obtained without prescription. And in 2017 the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety added to Stilnox a disclaimer that it may cause "nervous or psychological symptoms," noting also a possible correlation with "suicidal behavior".

Nowadays my mother is prescribed Alprazolam (a.k.a. Xanax), a kind of anti-anxiety medication. She doesn't like how it makes her feel the next day, and has found a different solution.

"[My friend] bought a good sleep mat, which is made of a kind of magnetic stone broken into sand, actually, and they put it in inside the mattress."

"So some kind of ground metal?" I ask incredulously.

"Yeah, and they fit it inside the mattress. And they believe that makes a good magnetic field around and underneath your body."

To my skepticism, she has bought one and is so far very satisfied.

Mainstream bedding and mattress companies are also offering services so that customers can create the optimal sleeping environment. Sleep-inducing drinks—one, sold by the food and beverages giant Lotte, is called Sweet Sleep—began appearing on the market in 2014. Sleep cafes where one can go and pay by the hour to nap started popping up a few years ago. One estimate has it that the entire sleep industry in Korea was worth 3 trillion KRW (2.5 billion USD) already in 2019 and is growing.

A subset of this industry is made up of digital products. When I mentioned reporting on Korea's sleep problem, a media expert acquaintance told me to try searching for sleep-inducing music in Korean on YouTube, and indeed there are more videos than I can count.

Another corner of the market consists of meditation apps, of which Kokkiri and Mabo are the best known. Kkokiri was founded some two years ago by Daniel Tudor, a former Economist correspondent-turned-author and businessman; and Haemin Sunim, a celebrity monk who authored the global bestseller The Things That You Can See Only When You Slow Down. (Full disclosure: I know both of them personally.)

While meditation wasn't originally intended for inducing sleep (far from it, seasoned meditators guard against falling asleep during their practice), even Daniel recognizes that in Korea meditation may be seen as a tool for getting a better night's sleep.

"Korea is, obviously, kind of notorious for a high incidence of depression and stress, and also a lack of sleep. So one of the big plus points of meditation is it can help you sleep better. Korea has the lowest, apparently, number of hours of sleep per night among the OECD countries," Daniel tells me.

Someone who isn't so enthused about the use of digital products for addressing stress and sleeplessness is Lee Sungkyu, CEO of Mediasphere and an industry watcher of all things digital in Korea.

"People who are looking for this kind of solutions, they are desperate," he says during an interview in his Myeong-dong office.

"It's important that they can find solutions that are close to them and convenient. But at the same time the main reason for the kind of stress or anxiety is structural and systemic. What that means is they should be encouraged to raise their voices and try to find solutions to these larger societal problems, rather than thinking of them simply as individual issues to deal with on a personal level."

In his view, apps that purport to help stress and anxiety go away for an hour or two "aren't necessarily bad, but this digital mindfulness industry that makes one close one's eyes to structural problems are cruel."

Even Daniel at Kokkiri admits that there may be limits to what his app can achieve. "I don't have the power to solve those problems," he says. "What we're doing or what any of...these kinds of practices is giving you is somewhat defensive, like a shield against these problems."

"People who are looking for this kind of solutions, they are desperate."

What are these structural problems that people are up against? Jieun, a 29-year-old female interviewee (who also happens to be a friend and former coworker), mentions impossibly long work hours and unreasonable demands on personal time by employers. Lee Hye-ri, a 54-year-old woman who recently quit her job at a big company, explains, "The reason was stress. I thought that if I stayed longer I had a lot to lose. I thought I would lose myself, I would lose my health."

Daniel at Kokkiri adds, "There's a heavy burden upon a lot of women in Korea. And so we do find that there's a lot of women who want at least just a feeling of a break."

Helping them is becoming big business. One major player is Buddhist temples, which have been offering a program called Templestay since 2002. Initially Templestay was conceived as a form of accommodation for foreign tourists in the Korean countryside where there were not many hotels.

In the last few years Buddhist monks realized that more Koreans are drawn to the program than foreigners are, and started to diversify their offerings, going so far as to divide them into the "activity" and "rest" categories, with the latter being stripped of Buddhist components that might put non-Buddhists off.

I visit one Templestay program at Hwagye-sa, a temple at the far northern end of Seoul. In reply to a question about what the Buddhist expression "letting go" means during a dharma talk, the abbot tells the guests:

"Look at the example of cryptocurrency. You can buy it, but as to whether the price goes up or down, that's not up to you as an individual.

"Just like that, many things in life they are not up to you. They are up to society. Society determines whether you can have success or not. And it's important to try not to get attached to the results that are beyond the realm of your control."

What he says is relatable, but it made me wonder, if people shouldn't put importance in things beyond their own control, does that mean that we can only deal with problems at our personal level? Is there no way to tackle the larger issues in society?

"Look at the example of cryptocurrency. You can buy it, but as to whether the price goes up or down, that's not up to you as an individual."

In fact, what I notice from talking to Daniel, Sungkyu and even the abbot at Hwagye-sa is how often younger generations—especially women—are mentioned as the demographic that has it the hardest. A surprisingly large number of Templestay participants look like they are in their late twenties or early thirties. Sungkyu says women in their twenties suffer the most from stress and anxiety in today's Korea. Daniel says a large segment of his app users are women in their thirties and forties.

There is something profoundly wrong with Korea today—especially when it comes to how younger women feel about their lives—and it's manifesting itself partly as sleeplessness. Dr. Lee at Dream Sleep Clinic and even the Templestay program may be offering much needed help, but it's worth asking: will these services be enough to fix problems that seem to go beyond simple individuals?

For more on the topic, listen to the episode "Sleepless in Seoul" of the BBC World Service series Crossing Continents.